Palliative care case study answered

This assessment task relates to the PCC4U Case Study of Tom, and incorporates learning from Focus Topic 2 (Caring for Aboriginal people with life limiting illness) in the online learning modules. In addition to your online learning, this content is covered in Seminar 2 (Week 10).

Tom is a 55 year-old Aboriginal man with advanced metastatic lung cancer. He collapsed at home, his family called the ambulance and he was admitted to the ward, extremely breathless. His disease is now end-stage. Tom’s wife Cec and their son Jimmy are with him in the ward. Tom’s main issues are pain and breathlessness.

The case study requires you to:

- review the concepts and principles of palliative care;

- think critically about the health needs of the person and their family;

- demonstrate your ability to understand the experience of the person with a diagnosis of a life-limiting condition; and

- demonstrate an evidence-based approach to assessment and clinical decision making for the people involved in this case study

What you need to do:

Write an essay that discusses an appropriate plan of care for Tom and his family. This essay should address the following points:

- Discuss two (2) of the relevant principles of palliative care that are applicable to the case study;

- Describe the appropriate nursing assessments for the two (2) symptoms (pain and breathlessness) that Tom is experiencing;

- Discuss three (3) evidence-based interventions (at least 2 must be independent nursing interventions) for managing each of the two (2) symptoms that Tom is experiencing (pain and breathlessness) that are culturally acceptable to Tom and his family;

Provide a description of how you would monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions within the context of palliative care;

Consider Tom and his family’s cultural needs and suggest culturally appropriate approaches to communicating with Tom and his family. The emphasis is on a clear understanding of the individual’s palliative care needs and the context of care. Your work should demonstrate an evidence-based approach through the use of current, reliable and relevant literature (including systematic reviews, and other evidence-based literature).

Patient’s End-of-Life Care Plan for Metastatic Lung Cancer

Name:

Student Number:

Institution:

Instructor:

Course:

Word Count: 2071

Date:

The Palliative Care Principles

There are many essential principles in palliative care. In this circumstance, most of the concepts would still be relevant. A palliative approach would be appropriate for Tom since his advanced stage metastatic lung cancer necessitates this kind of therapy (MacDonald and colleagues, 2021, P. 26). A nurse’s capacity to handle pain is one of their most critical skills and principles of palliative care. Indeed, pain is multidimensional, having a variety of distinct aspects to it (Cruz-Oliver, 2017, P. 110-115).

The World Health Organization’s ladder of pain management is the most effective way of relieving pain. With or without opioids, codeine or more potent opioids like morphine may be utilized and non-opioids (Altilio et al., 2019, p. 535-568). A wide range of issues must be considered, including those related to one’s mental, physical, social, and spiritual health. Many ethical, cultural and spiritual factors must be considered while coping with Tom’s grief (Sholjakova et al., 2018, P. 739-741).

Because Tom is an Aboriginal man who adheres to his people’s conventions, rituals, and culture when it comes to death and dying, his chosen method of pain treatment may be traditional methods, which may involve the usage of herbal medicine. These are conventions and practices that most healthcare employees may not be aware of but must be taken into consideration and observed. It is possible to alleviate a load of impending sadness and death by providing Tom and his family with pain medication that they are comfortable with following their traditions (Givler & Maani-Fogelman, 2019, P. 2). It would include treating Tom and his family with dignity and respect, irrespective of if he accepts or rejects pharmacological therapy and therapies.

In Tom’s case, another palliative care principle that would be applicable is connecting the family; patients inclusive, to structural support that would help the family and the patient cope and manage the patient’s illness as well as the family’s grieving and bereavement process (MacDonald et al., 2021, p. 275).

A health provider can refer their family to local Aboriginal support organizations that can help with the family’s social and emotional well-being while also honouring their customs and practices in the context of death and dying., as well as their religious beliefs. (Becqué et al. 2019, p. 28-39) describe situations in which a health care provider is not aware of the traditions of death or dying as per aboriginal culture. They are much more aware of and knowledgeable about the traditions of death and dying than the general public (Spelten et al., 2021, P.10). In addition to being a beneficial complement to the team providing palliative care to the patient, this is since they are culturally sensitive to the appropriateness of the treatment delivered.

Therefore, it would be simpler to provide traditional appropriate assistance to the family and their patients throughout the sickness, at the recovery period, and after death (Givler & Maani-Fogelman, 2019, P. 2). When the patient’s cultural beliefs and practices are included in the patient’s treatment, the family will feel more appreciated and supported since the patient’s cultural characteristics are being considered. It is the liaison officer’s responsibility to assist in the direction of patient care and give emotional and social care to patients and families to make them feel more at ease. This is a critical job, mainly when clinical health staff are inexperienced with or unaccustomed to the patient’s habits. (Spelten et al., 2021, P.10). The inclusion of one as soon as Tom was hospitalized is highly advised in this specific circumstance to assist in directing treatment that’s of cultural incorporation to provide support.

Nursing Assessment of Pain and Breathlessness

One of the most prevalent symptoms and indications of many illnesses and conditions is pain, especially in the elderly. It is evaluated in various ways depending on the factors listed below (Nuraini & Gayatri, 2017, P. 10). The onset of pain denotes when the pain is at its most intense and might be based on a certain period, such as in the mornings or evenings. Pain location, which is at any-body area, is vital to determine. The duration of the pain, which would then go into detail about how long the agony lasts. The patient describes the kind or nature of their pain, such as if it is dull or acute. There is an investigation into relieving or inciting variables, which goes into detail about things that create pain and those releasing it, which might encompass particular occupations or postures, respectively. Pain degree is also considered under the pain evaluation process and its impact on sleep, mood, and other important daily activities such as cooking and cleaning (Nuraini & Gayatri, 2017, P. 10).

In most cases, patients report breathlessness as difficulty in acquiring enough air, and it may be characterized by quick, shallow breaths. Dyspnea (inability to breathe) may be characterized as the main symptom of this condition (Hutchinson et al., 2017, P. 17). The nurse often assesses breathlessness by observing the patient’s breathing patterns, rate, and rhythm. Counting and obtaining the respiratory rate are two common uses of this technique. The nurse keeps track of the patient’s breathing rate for a full minute by seeing the chest cavity rise and fall. You may have tachypnea which is fast breathing if your rate is higher than the average, between 18 and 22 breaths per minute.

One of the most prominent indicators of breathlessness is that patients can not talk without stopping to take a breath. This is readily noted when one opens a discussion with the patient that necessitates the patient to provide a vocal answer (Hutchinson et al., 2017, P. 17). A common symptom of breathlessness is the use of deep laboured breathing. This is a compensating mechanism designed to inhale as much oxygen as feasible. Because most patients describe their dyspnea as a feeling of not having enough oxygen or suffocating, it is essential to observe deep laboured breathing in patients experiencing breathlessness (Birkholz & Haney, 2018, p. 219-227). A typical trait noted in people who breathe via their mouths is the usage of their abdominal muscles and neck muscles, particularly the sternocleidomastoid muscle, during inhaling. Patients’ extremities, such as their feet and hands, may appear blue due to a lack of sufficient circulating oxygen. When an oxygen saturation test is performed, it may reveal that the patient’s oxygen levels have reduced or have dropped significantly.

Nursing Interventions for Pain and Breathlessness.

It is possible to alleviate or treat patients’ complaints of suffocation and a lack of enough oxygen supply while experiencing breathlessness, which may be quite distressing for them (Birkholz & Haney, 2018, p. 219-227). Patients may be given oxygen treatment to increase the quantity of oxygen they get and attempt to compensate for the body’s oxygen needs. Sitting or fowlers or semi fowler positions should also be used to maximize lung expansion and oxygen delivery. Spirometers may demonstrate proper deep breathing techniques and enhance lung capacity, allowing the patient to get more oxygen (Senderovich & Yendamuri, 2019, P. 6). To guarantee optimal oxygen supply, the patient can be taught how to cough to clear the airway by expelling phlegm in case it is necessary.

Tom is a member of the Aboriginal community, and as a result, his methods of pain treatment may differ from those recommended by most medical professionals. Traditional or herbal medicines may not be easily accessible in the hospital. He may choose to use these instead. Tom’s discomfort may be relieved without pharmaceutical treatment to respect his culture and traditions. However, certain methods and movements can assist (Coelho et al., 2017, P. 1867-1904). Aboriginal officers may also be beneficial, as they may help design a plan of care that is acceptable in society to Tom and his family because they are well educated in their community’s culture and practices. Consequently, palliative care plans for Tom’s discomfort and breathlessness will be established following his wishes, an essential part of his treatment (Head et al., 2018, P. 23-29). There are several ways to alleviate pain using some of the measuring variables from the pain evaluation method.

Pain may be minimized by putting the patient in postures to ease his discomfort. It’s important to stay away from the triggers and stressors that exacerbate or intensify their pain. Removing these elements will provide them with respite or improve their ability to endure their pain (Su et al., 2018, p. 55). Patients should be able to fall asleep in a peaceful and relaxing atmosphere provided by the nurse. Most of the time, the discomfort is increased because of exhaustion (De Paolis et al., 2019, P. 280-287). Anticipating a patient’s desire for pain relief and acting quickly to meet that need helps the patient cope since early interventions make the patient feel cared for and concerned.

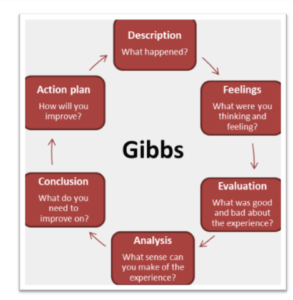

Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Interventions

Evaluation is a vital component of nursing. The nurse and other health professionals analyze and determine whether the measures are working, evaluating if they need to be changed to maintain things stable or raise them. In this scenario, I would first and foremost analyze and monitor the patient’s vital signs in order to evaluate the treatments (Van den Block et al., 2020, P. 233-242). Pulse, temperature, blood pressure, saturation and respiratory rate of oxygen in the blood. Pain management methods may stop functioning if the patient’s pulse and blood pressure rise beyond the normal range, and if they do, this implies that the patient is not in any discomfort.

To indicate that interventions to alleviate or reduce shortness of breath are not working, the respiratory rate should be greater than 22 breaths per minute, shallow and rapid breathing should be observed, as should the patient’s inability to speak as they pause to breathe and a decreased oxygen saturation level (Li et al., 2018. P, 26). Dyspnea indicates that the patient is improving and that the therapies are effective if symptoms reduce. As part of the evaluation process, the patient and family members may vocally describe how the patient’s symptoms have improved or worsened. To determine whether or not the treatments are effective, it is helpful to compare the outcomes of interventions to the specified objectives and anticipated patients outcome.

Culturally Appropriate Approaches to Communication

The essential central part of caring for patients is effective communication. Discussing the condition with patients and caregivers and gathering information that helps develop a diagnosis or the patient’s chosen treatment style are some of the uses of this tool (Brighton & Bristowe, 2016. P, 466-470). Communication is critical in palliative care because it allows providers to gauge the well-being of patients and their wants and needs and provide them comfort and support. It may be challenging to communicate effectively with Tom since he is Aboriginalian, a native community that does not identify English being their first language. If the patient’s native language is not English, the nurse may learn a few words to assist them in comprehending better.

In this case, using an Aboriginal Liaison Officer is also advised to aid the health care practitioner develop skills for relating to a patient while still honouring their culture and traditions (Smith et al., 2017. P, 23). Furthermore, the healthcare giver might use the officer to study and interpret the patient’s body language. As a result, they will be able to communicate effectively with the patient by using proper body language and understanding the patient’s body language. Assuring the patient that they have been heard and are being cared for is another important aspect of providing excellent customer service. When communicating with a patient or their family, it’s critical to avoid medical jargon and speak so that the patient and their family can comprehend (Brooks et al., 2018, p. 383-391). This is due to the fact that it will help the patient and their family understand the disease’s prognosis while also being culturally sensitive by outlining how and with whom information should be conveyed.

Establishing a relationship with the patient and their family will facilitate communication since the family, and the patient will get to know each other better and be more open to the nurse or health care professional sharing information about the patient’s health care plan (Smith et al., 2017. P, 23). Non-indigenous caregivers must work hard to establish trust and a strong connection with indigenous communities in ways that foster proper communication in Tom’s case because indigenous communities are often sceptical of non-indigenous healthcare personnel due to a history of mistreatment.

References

Altilio, T., Otis‐Green, S., Hedlund, S., & Fineberg, I. C. (2019). Pain Management and Palliative Care. Handbook of Health Social Work, 535–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119420743.ch22

Becqué, Y. N., Rietjens, J. A. C., van Driel, A. G., van der Heide, A., & Witkamp, E. (2019). Nursing interventions to support family caregivers in end-of-life care at home: A systematic narrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 97, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.011

Birkholz, L., & Haney, T. (2018). Using a Dyspnea Assessment Tool to Improve Care at the End of Life. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 20(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000432

Brighton, L. J., & Bristowe, K. (2016). Communication in palliative care: talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 92(1090), 466–470. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133368

Brooks, L. A., Manias, E., & Bloomer, M. J. (2018). Culturally Sensitive Communication in healthcare: a Concept Analysis. Collegian, 26(3), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.09.007

Coelho, A., Parola, V., Cardoso, D., Bravo, M. E., & Apóstolo, J. (2017). Use of non-pharmacological interventions for comforting patients in palliative care. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(7), 1867–1904. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2016-003204

Cruz-Oliver, D. M. (2017). Palliative Care: An Update. Missouri Medicine, 114(2), 110–115. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140030/

De Paolis, G., Naccarato, A., Cibelli, F., D’Alete, A., Mastroianni, C., Surdo, L., Casale, G., & Magnani, C. (2019). The effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation and interactive guided imagery as a pain-reducing intervention in advanced cancer patients: A multicentre randomized controlled non-pharmacological trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 34, 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.12.014

Givler, A., & Maani-Fogelman, P. A. (2019). The importance of cultural competence in pain and palliative care. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493154/

Head, B. A., Song, M.-K., Wiencek, C., Nevidjon, B., Fraser, D., & Mazanec, P. (2018). Palliative Nursing Summit. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 20(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000406

Hutchinson, A., Pickering, A., Williams, P., Bland, J. M., & Johnson, M. J. (2017). Breathlessness and presentation to the emergency department: a survey and clinical record review. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0396-4

Li, P., Guo, Y.-J., Tang, Q., & Yang, L. (2018). Effectiveness of nursing intervention for increasing hope in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis 1. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 26. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1920.2937

MacDonald, C., Theurer, J. A., & Doyle, P. C. (2021). “Cured” but not “healed”: The application of principles of palliative care to cancer survivorship. Social Science & Medicine, 275, 113802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113802

Nuraini, & Gayatri. (2017). Comfort Assessment of Cancer Patient in Palliative Care: A Nursing Perspective. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 10, 1–209. https://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/24_tuti_original_10_1.pdf

Senderovich, H., & Yendamuri, A. (2019). Management of Breathlessness in Palliative Care: Inhalers and Dyspnea—A Literature Review. Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal, 10(1), e0006. https://doi.org/10.5041/rmmj.10357

Sholjakova, M., Durnev, V., Kartalov, A., & Kuzmanovska, B. (2018). Pain Relief as an Integral Part of the Palliative Care. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(4), 739–741. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.163

Smith, K., Fatima, Y., & Knight, S. (2017). Are primary healthcare services culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people? Findings from a remote community. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 23(3), 236. https://doi.org/10.1071/py16110

Spelten, E. R., MacDermott, S., Morgan, S., Mitchell, L., & van Vuuren, J. (2021). Palliative Care in Rural Aboriginal Communities. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000801

Su, A., Lief, L., Berlin, D., Cooper, Z., Ouyang, D., Holmes, J., Maciejewski, R., Maciejewski, P. K., & Prigerson, H. G. (2018). Beyond Pain: Nurses’ Assessment of Patient Suffering, Dignity, and Dying in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(6), 1591-1598.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.005

Van den Block, L., Honinx, E., Pivodic, L., Miranda, R., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., van Hout, H., Pasman, H. R. W., Oosterveld-Vlug, M., Ten Koppel, M., Piers, R., Van Den Noortgate, N., Engels, Y., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Hockley, J., Froggatt, K., Payne, S., Szczerbińska, K., Kylänen, M., Gambassi, G., & Pautex, S. (2020). Evaluation of a Palliative Care Program for Nursing Homes in 7 Countries. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5349

Online nursing Essay Writers

Online nursing Essay Writers